When

People Meet

Animals

A production of the

Alaska Bilingual Education Center

Of the Alaska Native Education Board

4510 International Airport Road

Anchorage, Alaska

1975

Written by

Patricia H. Partnow

Illustrated by

Jeanette Bailey

6-75-500

TABLE

OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER I "Nihts'iil"

CHAPTER II "The Female Beaver"

CHAPTER III "First Salmon Story"

CHAPTER IV "A Bear Hunt"

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

Nits' iil

During the spring, Upper Tanana Athabascans

used to gather nihts'iil, which are little roots that muskrats find

and hide in their caches. One day a little girl found one of these

caches on a lake and took out all the nihts'iil to take home to her

family. She was very excited and very proud of herself when she got

home with the tasty food.

"Mom!" she said, "I found a muskrat cache!

Here's some nihts'iil."

"You've got to pay for the nihts'iil, " her

mother said when she saw the pile of roots. "Don't forget to leave

something in the cache for the muskrat."

"Oh, Mom," her daughter answered, "who would

ever know! The muskrat wouldn't know that I was the one that took the

nihts'iil. What does it matter?"

"Yes," her mother answered. "The muskrat will

know. You've got to pay for what you take. The muskrat worked hard to

fill his cache, and you shouldn't empty it without paying for

it."

The daughter still wasn't convinced. "What

happens if I don't pay for it?" she asked. The mother answered, "If

you don't pay, the muskrat will go into our cache, and take out all

our meat."

The little girl went back to the cache and

left a bit of cloth for the muskrat.

(Adapted from Guedon's People of Tetlin.

Why Are You Singing?1974: 47-48.)

CHAPTER II,

"The Female Beaver"

There is a Koyukon story that the old people

used to tell to their grandchildren on winter nights, when all the

children were warm between fur blankets. The fire in the middle of

the winter sod house would be burning low and the smell of the smoke

would blend with the smell of fresh spruce boughs covering the

floor.

The story went something like this:

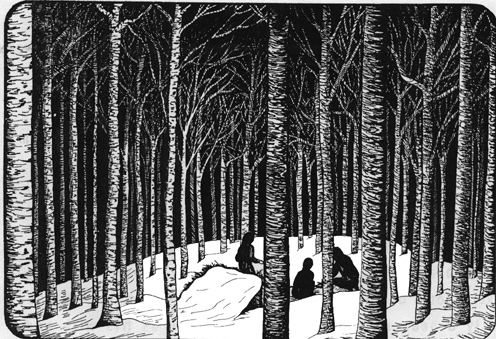

A young man was coming home from a

hunting trip late one winter day. He had been walking through deep

snow all day and was very tired, but decided to keep walking until he

got back to camp. He walked and walked, but didn't see any of the

familiar signs of home. He suddenly realized that he was lost.

It was dark by now, but he kept walking,

hoping that he would find the camp of another band. Then, he saw a

fire through the trees. There was a camp ahead, next to a lake. He

started running toward it, and when he got to the camp, was happy to

see people, at last!

The man was greeted by the people. They told

him that though they looked like people to him, they were really

beavers. He had strayed out of human territory and into beaver

land.

The young man was very tired. He looked around

at the beavers' camp. He saw a pretty young woman next to one of the

houses. Although he knew she was really a beaver, he decided to take

her as his wife and to stay in the beaver camp. He lived there all

winter long, with his new wife and her relatives.

When spring came, the young man knew that it

was time to go back to his own home. But springtime is the time of

hunger, and the beavers had no extra food to send with the young man

for his trip home.

The beaver-people talked it over. They

could not give the man food from their caches, but they decided they

would let him take one of their children as food for his trip.

The young man's wife offered to be killed. She

would become food for her husband and keep him alive.

Her parents looked at their son-in-law and

said to him, "When you have finished with the meat, you must throw

the bones into the water, and say 'Tonon Litseey'." This means "be

made again in the water".

The young man agreed, and set off for his home

village with the beaver meat.

The man got home safely, thanks to the meat he

had been given. When he had eaten it all, he threw the bones into the

water and said, "Tonon Litseey."

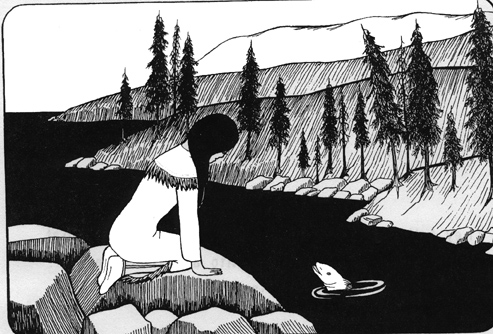

Suddenly the female beaver who had been his

wife appeared in the water where he had thrown the bones.

She swam away to her parents' lodge.

The old people would end their story by

saying, "And ever since that time, we have followed the custom of

throwing beaver bones into the water after we have eaten the

meat."

(Adapted from Sullivan's The Ten'a Food

Quest, 1942: 107-108.)

CHAPTER III

"First Salmon Story"

The Tanaina Athabascans used to tell a story

about a salmon. It goes something like this:

One spring day when it was just about time for

the salmon run to begin, a rich Tanaina man put out his fish trap as

he always did at that time of year. He hoped to catch enough salmon

to last his family for the whole year. The man told his daughter not

to go near the fish trap.

His daughter was curious. She wondered why her

father did not want her to see the trap. So, instead of obeying him,

she walked down to the river toward the trap. "Ill be back in a

little while," she called to her father as she walked away.

When the girl got down to the river, she went

straight to the trap. A big king salmon was swimming around in the

water, and she started talking to him.

They talked and talked, and before she knew

what was happening, she had turned into a salmon herself! She slid

into the water and disappeared with the big king salmon.

The girl's father looked everywhere for his

daughter. He could not find her. Every day he called her and searched

for her, but she never returned.

The next year, when the salmon run was about

to start again, the rich man set out his fish trap as usual. The

first time he checked it, he saw that it was fill with many beautiful

salmon. The man threw them all out on the grass, and began cleaning

them. He left the smallest fish for last.

Finally, all but the last small fish had been

cleaned. The man turned to pick up the little salmon --and saw that,

where the fish had been, there was now a little boy!

The man walked around the boy, staring at him.

He walked around him three times. And finally, the third time, he

knew why the boy looked familiar. He looked just like the man's lost

daughter. The man suddenly knew that this young boy was his grandson,

the son of his missing daughter.

The boy finally spoke to his grandfather. He

told him all the things he should do to show his respect for the

salmon. He told the man how to cut the sticks to dry the salmon, and

how to be careful not to drop the salmon on the ground while they

were being dried. And he told the man that each year, when the first

salmon of the year was caught, the people should hold a ceremony for

that salmon. They must wash themselves, and dress up in their finest

clothes. They must find a weed near timberline, and burn it. And they

must clean and cook the first fish without breaking its backbone. The

insides must be thrown back into the water.

The boy explained that if the man and his

people did all these things, they would have a good year, and would

catch many salmon. But if they did not follow the rules, the salmon

would never return to them.

The Tanaina used this story to explain to

their children how the First Salmon Ceremony got started and why it

was performed each year in the springtime. The people did everything

the young salmon-boy had told his grandfather to do.

(Adapted from Osgood's The Ethnography

of the Tanaina, 1966: 148-149.)

CHAPTER IV,

"A Bear Hunt"

A Koyukon Athabascan man and his son had been

out hunting one winter day. On the way back to camp, they discovered

a bear hole. The older man stuck the end of his long bear spear into

the hole, hoping to wake the bear up and make him leave his hole. He

poked and poked, while his son stood nearby with his own spear ready

to stab the bear as it came out of the hole.

The bear started growling. The man felt him

moving about -- he was going to come out! As the big animal emerged

angrily from his den, the two men panicked.

The son lunged at him with his sharp-pointed

spear. His father followed with another stab at the bear. There was a

struggle -- and the bear fell down, and slid back into his

den.

The two men were horrified. They knew that

after a bear has been killed, its forepaws must be cut off, and its

eyes must be burst. Although the bear was dead, its spirit, or yega,

could still harm the men if these things were not done.

The man and his son tried to remove the bear

from the hole, but it was already dark by this time and the bear was

very heavy. They could not pull it out.

The men returned to camp. They felt very

worried. because they had not followed the rules. The bear's yega

would be angry. Days and weeks went by, and nothing bad happened to

either one. Finally, they forgot about the dead bear in its

den.

A year later, the son went blind. The people

in his band said he had gone blind because he had broken a rule--he

had failed to burst the bear's eye after killing it.

(Adapted from Sullivan's The Ten'a Food

Quest, 1942: 86.)