|

Alaskan Eskimo Education:

A Film Analysis of Cultural

Confrontation in the Schools

5/The classrooms on

film

TULUKSAK, AN ISOLATED BIA

SCHOOL

Tuluksak was the smallest and most remote Eskimo village

in our study. It had been selected because informants in the Chemawa

Boarding School in Oregon said it had more of the survival economies

than any other Kuskokwim village. I found upon arrival that there

was no winter trapping going on, except by the VISTA worker’s

Eskimo assistant. Most of the village was on some variety of

relief (which can he jeopardized by other sources of income)

and during

my winter visit there was literally no activity.

The BIA school

was a compound of two classrooms, cafeteria, adjoining multipurpose

room, dispensary, radio room, guest room, and quarters

for the teachers, whom we will call Mr. and Mrs. Pilot,1 since

the husband is an accomplished flyer. This couple had been teaching

in

Alaska twenty years and so might he considered representative

of the BIA school culture.

Lower Grades

Mrs. Pilot was in command of a neat, well-equipped,

and efficient classroom of about twenty students. The style of

teaching was

structured and very verbal. The teacher spoke distinctly

in a well-modulated

voice and kept the class going at a regimented pace. From

a conservative point of view, this was a very well-taught class

that should

inspire a budding student teacher and delight educational

superiors. Indeed,

Mrs. Pilot’s teaching was spoken of with admiration

up and down the river and in faraway Chemawa.

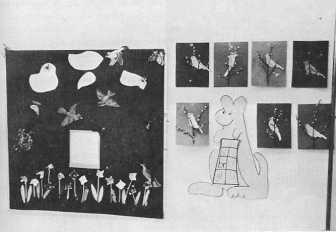

April and May

are bleak Arctic months on the Kuskokwim, but

much schoolroom decoration follows the seasons of the South.

Springtime

in the “Lower Forty-Eight” is the motif for this

bulletin board in the Tuluksak BIA school (below).

In response

to this verbal performance the students were

very quiet, though fidgety with what might be boredom or

withdrawal.

They were

well trained in their classroom roles, but looked a bit sleepy

and as students, would be called dull. The team judgment

describes the

class as overstructured and overtrained in proper behavior,

simply because there seemed no variation of behavior and

very little

spontaneous feedback from the students to the teacher or

to one another.

One variation in the class routine was filmed.

Once a week an old man from the village would come and tell

stories in

Eskimo.

On

this particular occasion the teacher set up the recorder

to tape the story

and then for a period left the room. Child-to-child communication

changed. While they were intently listening to the Eskimo

storyteller, the children formed a warm communicating group,

expressing

their acceptance of each other by body contact, hair caressing,

and

hand clasping.

Later the teacher brought in two Eskimo-made

models of forest hunting camps, complete with canoe, meat cache,

and forest

tools. The children

were immediately involved in the models. But when the teacher

took a pointer and began to ask questions, they reverted

to classroom routine and waited and watched the lecturing-questioning

of the

teacher. Apparently the questioning distracted them from

the

model

rather

than stimulating them to look into the model. For a few

moments the teacher’s aide questioned the students, and they

looked vividly at the model with considerable group communication.

During

my visit this Eskimo teacher’s aide usually remained

very quiet, standing back or simply handing material

to the class. I am sure she was much appreciated by Mrs. Pilot,

but

Mrs. Pilot’s

own style of teaching was so set that there was only

limited work of a serious kind for her aide to do. Occasionally

the Eskimo

aide

did take students into the cafeteria for special instruction.

But considering Mrs. Pilot’s teaching load in this two-room

multigrade school, where there certainly was need for a real teaching

assistant,

why weren’t these women teaching together? Because

the aide didn’t have a credential? Or was there

simply no academic place for a Native teacher in the

BIA school?

These questions will be probed

more deeply in our conclusions.

Mrs. Pilot went to great

effort to have a colorful, freshly decorated room in

keeping with the seasons. There were

spring motifs (even

in deep Arctic winter in the month of March) and child-play

images: a choo-choo train hauling a long load of alphabets,

a cutout

line of circus figures, a calf drinking from a bucket

of milk, a hoard

with a huge bumblebee, and cutouts on a pinup board of

the proper diet-Spanish rice, bread, butter, milk, and

gingerbread,

actually

the menu for the school lunch. These were gay images

of childhood, hut they were not for Arctic children not

Arctic

environment.

One of Mrs. Pilot’s survival lessons is not how

to keep from getting lost in a blizzard but how to obey

green and red stop-lights in Anchorage,

taught with a full-size, green-yellow-red stop sign.

The White school is dedicated to bringing modern knowledge

to Eskimos. Mrs. Pilot

was teaching White survival. Probably the only inadequacy

of this “survival

in Anchorage” lesson was the absence of a balancing

lesson on survival within the Native world-an area probably

outside Mrs.

Pilot’s cultural insights.

Visually the shortcoming

in this room was that there was generally only teacher-to-student

communication.

There

was no sense of

a circuit interrelating everyone. Instead, the teacher

was the center.

She

moved about constantly, sending messages to individual

students; But the students were as if alone in the room,

barely projecting

to the teacher and communicating with each other covertly

or not at all.

Culturally relevant learning of English

stimulated by a model of an Eskimo camp in the BIA school in Tuluksak.

Even

this able and punctilious teacher did not manage to ruin on this

classroom. Yet, of all the BIA teachers

in

our sample,

Mrs. Pilot had the most interaction with her village

and had genuine

friendships with various Eskimo women. She was ambitious for her students to excel, while at the same time

discouraged about

Tuluksak and the future of her students. We can surmise

that despite

the fact that Mrs. Pilot was an outstanding teacher

in her own style, this did not appear to support the Eskimos’ style,

and that the students became much too uncommunicative and at

the same time

unreceptive.

Some time later I had occasion to film

free-play in the village, and there was spontaneity and spirited

behavior.

The low

pace of the classroom was replaced with delight and

intensity.

Upper Grades

Mr. Pilot directed his class with equally seasoned

professionalism. He appeared to have reduced education

to its rudiments

and leaned heavily on workbooks, which is not unreasonable

in

a mixed-graded

classroom. His manner was gentle, quiet, and limited

in verbal messages. He moved about the room constantly,

briefly

answering

questions and

correcting faults. In a quiet way he exerted his discipline,

and the classroom was as structured as the first-through-fourth.

He

was very relaxed and his students equally relaxed.

The research team

described this behavior as sleepy. The team feels

the students and teacher are just going through

the motions.

Actually

this quiet teacher may have been giving more than

the film reveals

in-terms

of education.

The walls of the classroom do reflect

Alaska. There

was a poster with samples of all fur-bearing

animals, pelts

glued

on with

the proper names of the animals. Above the blackboard

were cutouts of Alaskan animals and a fleet of

snowmobiles. Mr. Pilot is a

flyer,

hunter, and gunsmith, and probably the older boys

relate to him on

these skills. At least this was one bridge, and

the eighth-grade students seemed genuinely involved

in

their tasks.

But despite these shared interests,

the teacher stands aloof. He rarely sits down with

his students

and

usually is in a

state of

motion. Our data sheets record little direct

evidence of student-teacher relations, and it was observed

that the

workbook lessons seemed

to

require very few responses.

Despite evident competence,

here also was a chasm with but a slender bridge- hunting and a

flyer’s

involvement with the ecology-with a sense of great air space between

teacher and student. Communication

signals were very limited. The students did not

watch the teacher or signal eye responses to the teacher. They

did relate in a nonverbal

way to one another; as one observer noted, they “yawned

in unison.”

Why was there so little to show

for the human warmth of this school? Mrs. Pilot’s

kitchen door was always open, and women were

often stopping to chat or have coffee with her.

She was always simple and

cordial and warm. In the evenings she helped

run a weekly bingo game for the interested mothers

and regularly held advisory school board

meetings. In one meeting she stressed that soon

the BIA might give up its educational function

and the village might be expected to

run its own school through a school board. Yet

in the same meeting she read a long letter from

the superintendent of BIA education asking

whether the community wanted Native teachers.

She presented the question by assuring them that

there were not enough accredited Native teachers,

so that if they wanted Native teachers they would

have an unaccredited

school. Since the majority agreed they did not

want an unaccredited school, this amounted to

not asking for Native teachers.

Had there been

a formal path through the jungle of bureaucracy

to practical goals of ethnic and

ecological

survival

education, certainly

teachers like Mr. and Mrs. Pilot would teach

toward such goals. We have described how Mrs.

Pilot did

bring an

Eskimo storyteller

into

the classroom. She made him very welcome and

taped his Eskimo tales, which showed her appreciation

of Eskimo

stories she

could not even

understand. With explicit sanction from above,

maybe many bush teachers would begin reaching

out

to Native

teachers

on many

levels of content

and skill.

Hovering in the background of the dedicated

efforts to these two career bush teachers is the couple’s

shared conviction that there is little future for tiny Tuluksak

simply because

dollars and

affluence are sweeping Alaska and somehow this

progress spells doom for Eskimo communities. In a silent way maybe

Tuluksak Natives feel

this also, and so together teachers and students

do not have much future to work toward. If there were a realistic

future, probably

these two teachers would change spontaneously

the style of their teaching.

The Tuluksak case was one of the most

baffling of our Eskimo study because of the ineffectiveness

of

the

human potential

of this teaching

team; Mr. and Mrs. Pilot deserved their reputation

as outstanding teachers, but still the school

appeared failing

the community.

What was critically needed may be genuinely

beyond the present intent

and resources of the BIA or any White-administered

Eskimo school. Education for Native welfare-missing

from this

school as from

so many others- is inextricably involved with

the conflict between two cultures and life

styles.

Tuluksak is a community, but is its BIA school

a community school? Is the lethargy of the

community related to

the pace of the school;

or is the school the effect of the community?

If it were a community school, what could it

do for

an underdeveloped

community?

The community force in Tuluksak now

is the Moravian lay minister, an Eskimo from the Kuskokwim

Bay

region on

the Bering Sea.

His efforts of community development are

expressed in compulsive church attendance

and study of the Bible. The BIA school appears

in conflict with

this church leader, and he has been reported

to discourage community actions

by the school. Hence the school on one very

important level is isolated from the community.

In a similar

way the VISTA

worker

also ran into

conflict with the church and found that his community program was quietly ignored by

the village-to

a point where the

VISTA worker

just sat alone in his cabin. As already stated,

this is not always the case with BIA village

schools; occasionally they

have added

to the community welfare in positive ways-though

likely by circumnavigating BIA isolationism.

I

revisited Tuluksak on May 3, just on the eve of the river breakup,

indeed on the very

last

ski plane.

The

world was

pools of melting

snow, and great cakes of ice were beginning

to move toward the sea. The silent winter

village had sprung

to life

as more and

more navigable

water opened up along the village shore.

Everywhere boats were being caulked, outboard

motors repaired,

nets mended,

a canoe

re-covered. Muskrat season was about to

begin. Salmon fishing was weeks away.

Everywhere children ran, danced, played

marbles with young and old, played baseball, hovered

around the

water edge

watching winter go

out. Boats were finally launched in the

limited clear water and

motors began roaring as Eskimos raced up

and down “to shake loose

the ice.” At this season it was hard

to believe Tuluksak was doomed or had a low

ebb of vitality at all. There was fire in

Eskimo

cheeks and sparkle in their eyes. How could

there be a dull school in the midst of such

vitality?

1 Descriptive code names have been devised to

help the reader recall the many different characters in our drama.

|